Journal of Humanistic Psychology (2020)

Sohmer, O. R. (2020). The Experience of the Authentic Self: A Cooperative Inquiry. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 0022167820952339.

Abstract

This article presents the process and findings of a cooperative inquiry exploring the experience of the authentic self—a prominent theoretical construct in humanistic psychology and diverse spiritual traditions. Despite theoretical prominence and emergent psychological research interest, there has been little qualitative research into the authentic self as it is experientially encountered and lived. The present study addresses this gap in the literature using an experiential and participatory research approach. Seven co-inquirers joined in nine cycles of action and reflection over the course of 6 months to inquire, “What is my (the) experience of my (the) authentic self?” In collaboration with the co-inquirers, the initiating coresearcher generated six themes using thematic analysis in response to this primary research question: (a) presence and flow, (b) somatic awareness and vitality, (c) expression of truth, (d) multidimensionality and integration, (e) values and impulses, and (f) dynamism and relationality. In addition, the transformative and practical outcomes of the inquiry are discussed. Finally, several implications of these outcomes and suggestions for future research are outlined.

The Experience of the Authentic Self: A Cooperative Inquiry

Seeking, cultivating, and expressing the authentic self [1] is a major concern of many psychological and spiritual traditions. Humanistic psychology, perhaps most notably, popularized the value of authenticity and self-actualization through the work of Rogers (1951, 1961), Perls (1968; Perls et al., 1951), and Maslow (1954/1970). Strands of psychoanalytic thought (e.g., Miller, 1979; Winnicott, 1960) similarly postulated that the primary task of psychotherapy is recovering the authentic self, which can be repressed in childhood when the child’s natural desires, tendencies, and impulses conflict with the expectations of the caregivers and community on whom the child depends. The contention is that in adulthood the “real person,” in Rogers’ (1961) terms, may remain concealed or underdeveloped because of early relational and cultural conditioning, while liberating this authentic self is critical for well-being and vitality. Additional theories that intimate the necessity of cultivating one’s authentic self in the process of psychospiritual growth abound in the literature, including Jung’s individuation (Von Franz, 1964), Hillman’s (1996) acorn theory, Assagioli’s (1993) self-realization, Daniels’ (2005) transpersonal self, and Rowan’s (1993) Deep Self. This line of inquiry, of course, has deep historical roots in modern Western psychology (James, 1890) and beyond—visible in, for example, the ancient Greek maxim “know thyself” and the abundant philosophical discourse surrounding this teaching (e.g., Plato, 1892/2018). Related sentiments can be found in Eastern philosophies and spiritualities as well. Important trends in various Yoga traditions emphasize the discovery and fulfillment of one’s dharma, or unique purpose in life, suggesting that there is an authentic self from which one’s purpose unfolds (Feurstein, 2001). As the often-quoted Bhagavad Gita dictum states, “It is better to fail at your own dharma than to succeed at the dharma of another” (Cope, 2012, p. 69). Thus, albeit variously expressed,[2] the idea of an authentic self is persistent in the literature and reflected in widespread endorsement in popular culture (evidenced by hundreds of books featuring “authentic self” in the title; e.g., Brown, 2010; Joseph, 2016; Rosenberg, 2019).

Despite theoretical prevalence and popular endorsement, psychological research on the authentic self has been described as still emergent (Hicks, Newman, & Schlegel, 2019; Joseph, 2017), with qualitative and experiential investigations particularly limited. That said, there has been an influx of contemporary research that supports the significance of authenticity (notably documented in the special issue of the General Psychology Review dedicated to the topic; Hicks, Schlegel, & Newman, 2019). This emerging research has demonstrated correlations between alignment with the authentic self and psychological well-being (e.g., Kernis & Goldman, 2006; Lenton, Slabu et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2017; Rivera et al., 2019; Schlegel & Hicks, 2011; Wood et al., 2008), resilience (e.g., Bryan et al., 2017; Wickham et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018), and relationship satisfaction (e.g., English & John, 2013; Lopez & Rice, 2006; Neff & Suzio, 2006; Stevens, 2017). Understandably, attempts to conceptualize and define authenticity (e.g., Jongman-Sereno & Leary, 2019; Newman, 2019) determine the ontological status[3] of the authentic self (e.g., Baumeister, 2019; Rivera et al., 2019), and comprehend paradoxical research findings (e.g., participant reports of feeling more authentic when acting in accordance with external social expectations than with personal feelings and characteristics; Fleeson & Wilt, 2010; Lenton et al., 2016) are still in process. However, the subjective experience of feeling alignment with one’s authentic self (e.g., Baumeister, 2019; Chen, 2019; Rivera et al., 2019; Strohminger et al., 2017) and the corresponding psychospiritual benefits are well substantiated (see above).

The present study contributes to this conversation and the cooperative inquiry literature through the accounts of seven co-inquirers who engaged in a dynamic participatory research process to explore their authentic selves experientially. Bracketing ontological claims, the focus of this research is phenomenological (i.e., focused on the subjective, lived experience of co-inquirers’ encounters with what they identify as their authentic selves), participatory (i.e., contextual and relational), and transformative (i.e., concerned with the impact of the research process on co-inquirers with regard to the domain of inquiry). As discussed below, this process offered a meaningful opportunity for co-researchers to engage, reflect, and share about their experiences of their authentic selves, while generating insights to contribute to the theoretical and empirical literature on this subject, as well as illuminating opportunities for further research.

Cooperative Inquiry Methodology and Study Overview

This study uses Cooperative Inquiry (CI; Heron, 1996)—an experiential and participatory approach to qualitative research and learning about the human condition. In this method, a small group of co-inquirers (typically 6-12) engage in a series of collaboratively determined action and reflection cycles (usually a minimum of 8) to elucidate an inquiry domain of mutual interest. Immediate experience during the action phases (i.e., periods of intentional group or individual activity or experimentation conducted with heightened reflective awareness) is at the heart of the research data, which is later reflected upon to gather insights and inform subsequent inquiry cycles (i.e., a complete period of action and group reflection on that action). In the full form, co-inquirers join as co-researchers and co-subjects, including the initiating researcher(s) who may educate others about the method at early stages. CI can be conceived of as an intersubjective, or relational, phenomenology comprised of recursive group experiments and reflections.

Throughout the process, attention is paid to the rigor of the inquiry through specific validity procedures, the quality of collaboration, as well as the emotional and interpersonal dynamics that may arise within the group (Heron, 1996; Heron & Reason, 2006). For example, efforts are made to foster genuine collaboration by supporting individual self-awareness and autonomy, making mutual decisions consciously, and inviting balanced participation among co-inquirers. Multiple ways of knowing (e.g., embodied, creative expressive, relational, intuitive) are intentionally cultivated in the context of an extended epistemology including conceptual/propositional, imaginal/presentational, experiential, and practical knowledge (Heron & Reason, 1997, 2008). Within this basic structure and holistic orientation, the specific actions undertaken by an inquiry group are open-ended (e.g., interpersonal, creative-expressive, and contemplative practices) and collaboratively selected to support the inquiry. Intersubjective knowledge is leveraged by fostering collaboration at all stages, which invites refinement of inquiry outcomes through discussion of divergent and shared perspectives. Finally, outcomes of CI are expected to be twofold (Anderson & Braud, 2011; Heron, 1996), with transformative outcomes (i.e., the ways in which engagement with the inquiry impacts co-inquirers) valued at least as highly as informative outcomes (i.e., conceptual responses to the inquiry question).

Inquiry Focus

The CI methodology was well suited for the experiential focus of the present study, which explored the experience of the authentic self. More specifically, I invited co-inquirers into the following primary research question: “How does a person on a path of psychospiritual growth experience his/her/their authentic self?” This question was refined through group discussion into: “What is my (the) experience of my (the) authentic self?” As highlighted in this variation, the group chose to foreground personal, subjective experiences of the authentic self, while staying open to general or shared understandings. Although we discussed our conceptualizations of the authentic self openly, we did not seek a common or predetermined definition of the term, instead leaving the meaning open to be personalized and evolving.

Participants

The inclusion criteria to participate in this study were being (a) self-identified to be on a path of psychospiritual growth, and (b) interested in exploring the authentic self. Co-inquirers were recruited from the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) and Hakomi Mindful Somatic Psychology training communities in San Francisco, including past and present graduate students and trainees. This recruitment pool addressed the need for co-inquirers to have some existing capacity to mindfully navigate and share inner experiences and collaborate within an intentional group (Heron, 1996; Lahood, in press). The group constellated as three men and four women between the ages of 25 and 65; six white and one self-identified as Hispanic, including two self-identified as Jewish and two immigrants; half affiliated with Hakomi and the other half with CIIS (including myself, the seventh member, representing both).[4]

As the initiating researcher—and only group member with prior experience with CI—I offered educational information about the method and facilitated the foundation of the process throughout (e.g., opening and closing sessions, guiding us to alternate between actions and reflections, checking in about inquiry quality at regular intervals). However, inquiry decisions (e.g., selecting inquiry actions) were made collaboratively from the beginning, and after the first full day session, other co-inquirers joined in facilitating opening practices and action phases. Finally, given the option to be anonymous or identified by name, co-inquirers chose to include their real names and identifying characteristics along with their accounts in the inquiry outcomes.

Procedure

The inquiry process took place over six months, including one three-hour introductory meeting, four eight-hour days of interactive group sessions, one online video reflection meeting, and a final half-day session when we met to discuss the preliminary inquiry findings. This included nine total inquiry cycles—five action phases conducted together and four that took place in our personal lives between meetings (see Table 1 for list of actions). Accounting for absences due to health reasons or schedule conflicts, co-inquirers engaged in 32-40 hours of group contact.

| Table 1 Authentic Self Cooperative Inquiry Action Cycle Summary | ||

| Cycle | Action Description | Duration |

| 1 | Group interaction: Engaging from our present moment experience while suspending the “socialized self” | 30 mins |

| 2 | Convergent daily life inquiry: Witness moments of authenticity or inauthenticity in daily life. Journal about what you notice. | 2 weeks |

| 3 | Repeat action 1: Group interaction | 45 minutes |

| 4 | Art making: Drawing or painting a visual map of our authentic selves and the parts within | 1 hour |

| 5 | Divergent daily life inquiry* | 2 x 30 mins within 2 weeks |

| 6 | Witness each other sharing about a topic of personal concern—those witnessing can offer questions or reflections to invite more authenticity from the one sharing | 15-25 mins each; 3 hours total |

| 7 | Divergent daily life inquiry* | 2 x 30 mins within 3 weeks |

| 8 | Divergent daily life inquiry* | 2 x 30 mins within 3 weeks |

| 9 | Silent nature walk with attention to self-awareness and connection, followed by non-verbal return to inquiry space and spontaneous music making | |

| * For example, spend time connecting with ones’ authentic self and act on the impulses that arise, spend time in nature exploring the experience of the authentic self in that context, dialogue with one of the parts drawn in action 4, repeat action 2, engage in an action/conversation that feels important for your authentic self, etc. | ||

All of our meetings took place at the San Francisco Bay Area homes of co-inquirers, with about 70% hosted by one inquirer in the Oakland Hills. We typically gathered in a circle, seated on the floor with a simple nature-based altar at the center. Our full days together included time to check in personally, engage in a meditative and/or embodied practice (the facilitation of which rotated), one or two group action phases, individual and group reflection periods, and periodic meta-reflections on the evolving inquiry process and outcomes. Together we engaged in a variety of actions including group dialogue with the intention to bracket the “socialized self” [5] (Lahood, 2019; Naranjo, 2004) and speak from immediate experience, group witnessing of individual self-expression around a topic of personal concern, making art visually mapping one’s authentic self, a silent group walk in connection with self and others, and spontaneous music making (see Table 1). Inquiry actions that took place in our personal lives were more individualized including self-observation and journaling about moments of perceived authenticity and inauthenticity, setting aside time to meditate on and follow the impulses of the authentic self, among others.

Validity Procedures

We followed the validity considerations outlined by Heron (1996), including research cycling (i.e., engaging in 9 action-reflection cycles in our case), balancing action and reflection, inviting convergence and divergence of inquiry actions (i.e., participating in the same action as a group versus taking different actions individually), inviting multiple ways of knowing into reflection (e.g., sharing created art during some reflection periods), attending to chaos and order (i.e., inviting spontaneity at times while also following an emerging plan), and tracking for potential unaware projections. On a fundamental level, we established group guidelines[6] at the beginning and agreed to share the responsibility of tracking and periodically checking in about the quality of our collaboration, inquiry, and relational dynamics. Finally, we employed the Devil’s advocate procedure (Heron, 1996), in which we selected a conceptual claim that we found particularly compelling and attempted to challenge it with alternative perspectives.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected in the form of audio recordings of group reflections, photographs of artwork, and reflective writing shared by email. Audio recordings were later transcribed by the initiating co-inquirer and compiled chronologically with written accounts. Although interrelated, the data analysis can be conceptualized as occurring at two levels: (a) ongoingly by the group through recursive action-reflection cycles and periodic meta-analysis regarding the inquiry question and our emerging responses, and (b) retrospectively by the initiating co-inquirer who used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to assess the complete dataset. Of course, these two levels of analysis are inextricable, as group inquiry analysis discussions were included in the transcripts that were retrospectively analyzed. Finally, the initiating co-researcher brought the preliminary outcomes of the thematic analysis back to the group for feedback regarding resonance and desired revisions. The presentation of findings in the next section incorporates co-inquirers’ feedback at this stage and has been approved by all co-inquirers.

Inquiry Outcomes

There is a sparkling image in the abyss. I see myself in that mirror and am unbound from prison, free to move in the world creatively. And with my heart open—though it’s sometimes painful—I will and encourage others to do the same. (Ashton)

The following presentation of outcomes emphasizes findings that respond directly to the primary research question, delving into a thematic analysis of the inquiry data addressing experiential accounts of the authentic self. Subsequently, I offer a concise account of transformative and practical outcomes of particular relevance for future CI endeavors and research into the authentic self.

Informative Outcomes

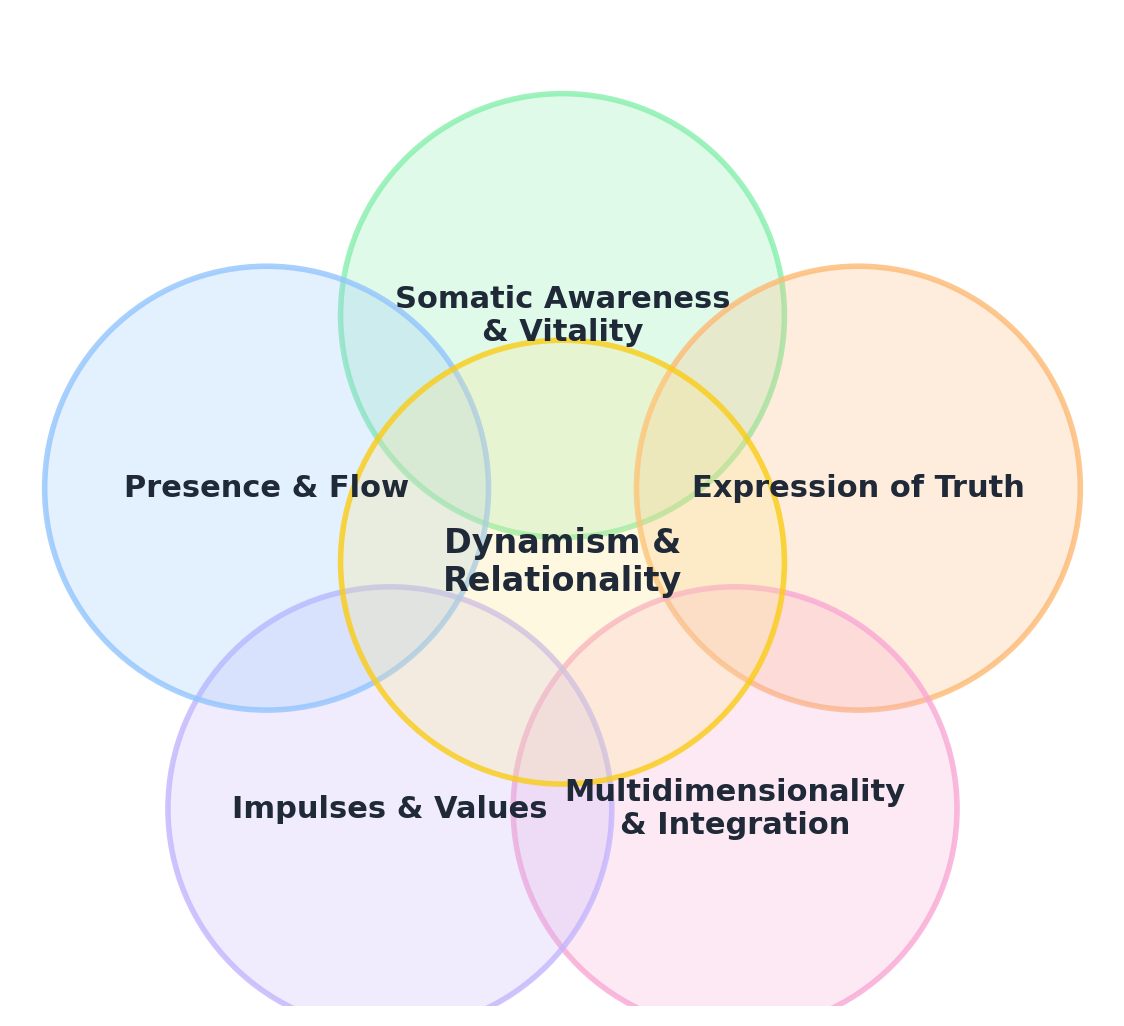

Thematic analysis of the inquiry data generated six major thematic categories in response to the primary research question: “What is my (the) experience of my (the) authentic self?” These categories are interrelated and often overlapping—connected yet distinct facets of a whole—including: (a) presence and flow, (b) somatic awareness and vitality, (c) expression of truth, (d) multidimensionality and integration, (e) impulses and values, and (f) dynamism and relationality (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Thematic Analysis Outcomes

Presence and Flow

At one point or another, each co-inquirer attributed the states of presence and flow to their experience of their authentic selves. Although we did not define these terms explicitly, the sentiment was of being aware and available to whatever was arising in the present moment. The quality of flow also suggested states of absorption and ease with whatever one was engaged in (see Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). As Erika, counselor and dancer in her 60s, described: “my body, mind, personality are not getting in the way of natural impulse and responsiveness to present time.” In contrast, Erika highlighted that “rushing” (i.e., anticipating the future with a sense of time pressure) was disharmonious with her authentic self. Relatedly, I characterized contact with my authentic self as: “feeling at ease with the way my experience and expression is unfolding.” Contributing an affective tone of satisfaction or contentment, Bill—a somatic teacher in his 50s—explained that he perceived the connection with his authentic self as: “Not blinded by my history, not hungry for someone or some experience, sustained fully from its own source, without need or attachment.” In contrast, Bill described:

When I catch myself in any sort of “doing-mode”… it doesn’t allow me to be in the organic unfolding of the moment, which is what I’m now looking at as authentic because that organization has promise and possibility, whereas the other is going to allow habit.

These statements speak to an experienced facet of the authentic self that appears to be sensitive and attuned to immediate experience in a way that feels easeful and fundamentally fulfilling—offering the “promise and possibility” of novel, emergent response and expression.

Matt, 34-year-old professor and philosopher, highlighted a related experience of the paradoxical state that he called “un-self-conscious flow” as a doorway to his authentic self:

[A]s I’ve gotten to know you more and we’ve been vulnerable… in sharing with each other, it makes me feel like I’m less stuck in myself and less worried about how my “self” is being seen. So, it’s as though when I’m not thinking about my authentic self, it’s easier to be that.

In sum, the experience of presence and flow could be applied to both the dynamic interplay between outer stimuli and relationships as well as to inner perception of oneself.

Somatic Awareness and Vitality

A complementary theme of somatic awareness and vitality was also prominent in co-inquirer accounts of the authentic self. Although interconnected, the two aspects of this theme are discussed in turn. First, co-inquirers reported in various ways that they perceived accessing and expressing their authentic selves based on embodied sensations or an intuitive “felt sense.” For example, Isabel, a 51-year-old coach, artist, and graduate student, described her connection with her authentic self as being a, “sense of alignment or flow in [her] body versus resistance [in her body]—a grating feeling.” In Isabel’s statement, the experience of “flow” comes through as an embodied sensation that indicates contact with her authentic self. I similarly reported that, “I feel it [my authentic self] in my body [and] resistance in my body comes when I’m inauthentic.” Corroborating this sentiment of having a felt sense of connection or disconnection with the authentic self, Bill contemplated:

I can feel it [the authentic self]… Like the true north. Because I know when I’m away from it… A Tai Chi teacher said that Chi cannot be seen, it can only be felt… I’m applying that to the authentic self, because all of us seem to have something that we’re seeing as “oh, that’s closer or farther from my authentic self…”

He summed up naming the “ineffable but felt” aspects of this experience.

Co-inquirers also emphasized the qualities of vitality throughout the inquiry, describing the experience of their authentic selves as a feeling of being “vibrant and alive” or tapping into a “well-spring of vitality” or “lifeforce.” For example, Ashton, a 26-year-old artist and graduate student, described that connecting with and expressing his authentic self during a group action he “felt more alive, his body getting warmer and sweating.” Later, he elaborated: “[I] Feel lighter, loosen my grip, speak with the fullness of my voice, blood circulates, not overthinking next steps.” In a related account, I reflected:

There’s an aliveness… When I feel like I’m rooted in and revealing myself authentically there’s… a heightened sense of being alive… I’m not sure how to describe it… it’s not like I’m vibrating but I’m just more present, I feel my body more, I’m inhabiting my body more… there’s a raw, vulnerable part to it that maybe enhances the sense of aliveness.

Thus, likely building on the foundation of presence explored within the first theme, this quality of vitality contributes a somatic dimension as well as a heightened energetic state to the experience of the authentic self as we explored it.

Expression of Truth

The third theme that was highlighted by co-inquirers revolved around the role of vulnerability and self-expression through emotions and “personal truth” arising from the experience of contact with the authentic self. From the beginning of the inquiry, we noted the qualities of being “uninhibited,” “bold,” “raw,” “open,” “honest,” and “vulnerable” as integral to authenticity, as well as the importance of knowing and “speaking one’s truth.” For example, Isabel stated clearly: “I feel that there’s something in me that wants to say something, and I feel that that’s my authentic self.” Importantly, in addition to what could be articulated in words, personal truth also included the full spectrum of emotions—from pain to joy. Highlighting the vulnerability inherent in this kind of self-expression, Bill eloquently reflected: “I feel most connected to authentic self through vulnerability. Through imagined flaws. At times, essence emerges through the cracks, as an echo of authentic expression.” Taken together, these accounts illustrate the intimate relationship between the authentic self and truthful expression—suggesting that such an expression is both an integral facet and function of the authentic self.

However, our understanding of the value and necessity of self-expression became more nuanced throughout the inquiry. Full expression as a rule was questioned, replaced instead by discernment and choice around when to “come forward” or “pull back.” Like the image of “a flower opening and closing,” we came to agree that the authentic self could be “subtle” and “cocoon-like” at times, and in this sense, not disclosing or expressing ourselves could also be authentic when it was a conscious choice. I reported a realization along these lines: “I don’t have to express the authentic self outwardly—it can be enough to feel it and the contrast helps me to discover myself.” I later elaborated:

I had this idea that there are parts of me that are somehow more authentic than other parts. But now that seems to dissolve. Because I noticed in that impulse to express myself “more authentically”… [is only] a part of me… there’s this kind of willful, almost aggressive impulse in that toward myself… to challenge myself to be “more true” or “real” in this moment. But… challenging myself to be more raw and vulnerable is only one part of my authenticity—because I… have a relational disposition also… I genuinely value social harmony. So, even if that means that maybe I’m holding back a little bit in an interaction for the sake of that, I still don’t feel like that’s inauthentic at this point.

In a closing reflection about the inquiry process as a whole, Ashton elucidated a similarly nuanced perspective regarding expression and withholding:

What surprised me the most was the value others attributed to the moments when I burst into tears… that reportedly freed up others to express more of themselves too. And yet, I also learned that sometimes it’s important to withhold one’s “authentic” expression to spare or allow another person to settle in some way. The latter example I think points to the ecological/collective aspect of authenticity, whereby—if necessary—my individual expression temporarily takes a backseat for the health of the whole.

Both of these accounts suggest that being aware of one’s genuine experience, or “truth,” is primary to maintaining a connection with the authentic self, while outwardly expressing that truth is secondary—open to discernment and contingent on the social context. In other words, we came to a shared sense that withholding self-expression does not necessarily disconnect, suppress, or betray the authentic self when it done with clarity and a sense of choice.

Multidimensionality and Integration

Deepening into the complexity and paradox of our inquiry, another significant theme explored the multiple dimensions or parts that we encountered in our experiences of our authentic selves and the integration of these parts into a coherent whole. Simply put, all co-inquirers variously acknowledged that their experience of their authentic selves brought them into encounters with multiple seemingly distinct yet interconnected parts.[7] Jill described like this:

I noticed that my authentic self is devised of many parts inside. Some of those parts feel more free than others to express their truth, depending on what sort of feedback/reflection those parts have received in the past. And there is no constant in my authentic self—it’s all changing, all the time, dependent on my parts inside, my general state of being, and the mood set by the group.

We came to a shared sentiment that allowing, liberating, or integrating parts that were previously suppressed or disowned based on cultural conditioning or childhood experiences was central to the process of cultivating our authentic selves. Among these were both the virtuous parts—that corresponded with qualities like the ones highlighted in the themes above—as well as difficult, immature, or painful aspects of ourselves.

This exploration widened the aperture of our inquiry, illuminating an interesting tension in evaluating or comparing the relative authenticity of different parts. On the one hand, we generally agreed that there were certain qualities, states, or attributes that we associated with our experience of our authentic selves. Yet on the other hand, we found it increasingly difficult to judge certain parts of ourselves and our behaviors as less authentic than others—a conundrum for our inquiry indeed! Bill aptly described his evolving perspective on this matter:

What I quickly realized was that I was categorizing the behaviors that I appreciate as authentic and the ones I don’t feel good about as “other.” The insight that comes with this awareness is that what I am doing in the moment, in part, is my authentic self. I don’t get to separate myself out into only the parts I want to represent as authentic. It is more real to include all of me. Because, like it or not, I am doing the behavior.

In this sense, we came to include the parts of ourselves that might be considered “false,” “strategic,” or “shadow” as also authentic within the context containing them. Of course, if taken to the extreme, this perspective issues a fundamental challenge to the viability of discerning one’s authentic self apart from all experiences or expressions. However, rather than nullifying our inquiry, this contemplation ushered us deeper into the paradoxical nature of the authentic self, highlighting the important dialectic between our “ideal” and “real” experiences of self. That is, we found our authentic selves in both the ideal qualities that we sometimes experienced as well as in the reality of all of our immediate actions and expressions—influenced by our wounds, perceived flaws, limiting patterns, and so forth.

Engaging this tension challenged us to forge a more expansive frame for what we came to identify as the authentic self. Erika offered an illustrative metaphor of a guitar. To paraphrase, while all expressions—even “flat” or “warped” notes stemming from a certain imbalance—are authentic to the guitar to the extent that they come from the same instrument, certain “organizations” allow more or less alignment with her authentic self. From this standpoint, we agreed that we could reflect on past experiences to discern our retrospective sense of “alignment” with an idealized version of the authentic self. Yet, at the same time, we found that all of our lived, immediate experiences—even when out of “tune” or alignment with the ideal—were also authentic in their own right. Thus, we decided that even if we can differentiate an ideal inflection of the authentic self from the myriad expressions that fall short, it felt important to welcome all of the parts of ourselves into the folds of what we identified as our authentic selves.

This radically inclusive stance toward the multiple parts or dimensions of the authentic self also evoked discussions of integration—the process of making conscious, validating, and incorporating the different parts of ourselves into a coherent whole. Much like shifting focus from figure to ground, welcoming all of the diverse parts within invited awareness of the greater whole that contains or unites them. Isabel described her evolving impression of cultivating a relationship with the authentic self as: “Taking all of these different aspects and integrating them into our personality,” and suggested “the more integrated we are, the more whole and complete and authentic we are.” Later, she offered a poignant image for the process of integrating past, especially challenging, experiences into the present reality of authentic self, inspired by seeing the fresh green buds growing through decaying vines:

Our relationship to the old… [is] also what feeds us. We wouldn’t be the people that we are without all these things fertilizing the ground that we’re growing in… All the dead matter, all the stuff that came before, is part of who I am. And it’s not something that I can do without. And it’s as important to my growth, to my sustenance… it really informs who I am today.

In line with this sentiment, our exploration of multidimensionality and integration contributed a dynamic impression of the authentic self as inclusive of ideal and real, virtuous and challenging. Within this framework, the ideal no longer dominated our impression of the authentic self but served as an orienting principle or integrative force to yoke the parts.

Impulses and Values

Another theme that came forward in our experiences of our authentic selves was the dialectic between impulses and values—often corresponding with the difference between immediate reactions and intentional responses. Although this theme could be considered a particular inflection of the interplay of parts as well as the real-ideal tension, its prominence in our inquiry called for a separate category.

Early on in our process, multiple co-inquirers grappled with the role of impulses in their experiences of their authentic selves. As Erika captured succinctly: “What does authentic mean? Is it my impulse? Is it my decision to moderate my impulse and come from a different place?” This line of thinking engaged two popular psychological notions regarding the authentic self: (a) the idea that immediate impulses are of primary authenticity, often overwritten by social conditioning, and in need of being liberated; and (b) the conception that the authentic self reflects higher, universal values, like love, integrity, and compassion over base impulses. Isabel contemplated along these lines during an inquiry action cycle when we set out to pay special attention to moments of perceived authenticity and inauthenticity in our daily lives:

I have been reflecting on what it means to be authentic. Is it acting/reacting without filter or engaging from the place of our higher self?… There is someone in two of my classes who annoys me… For the last recent weeks, I have been practicing sending her loving kindness and compassion instead of reacting to her with my usual irritation. Is that authentic? Or is the irritation my “authentic” response? Does authenticity require unfiltered or automatic behavior? Or can we bring our best selves, who we want to be, how we want to show up, to the equation and still be authentic?

Her account highlights the felt authenticity of immediate impulses or reactions while also emphasizing the capacity of her authentic self to choose a value-based response to life. I also explored this terrain while reflecting critically on the authenticity of my impulses themselves:

I might be following an impulse that feels most present in the moment but when I reflect on it, I realize… it was old material to some extent… I started to wonder… “to what extent is that authentic?” and “to what extent is that a groove or an eddy in my emotional landscape?” So a switch got triggered and I’m running that [past] script rather than being with myself… in the present… I feel like spontaneous impulse and expression feels alive and authentic and then I start to question to what extent I have… freewill in that. Or when does it become like a sort of possession state of old trauma or pattern or habit?

As these accounts convey, the experiences in which we felt alignment with our authentic selves did not primarily emphasize following and expressing our impulses.

However, in line with the radical inclusion of multiple parts, we did not come to a static conclusion that value-modulated responses were entirely characteristic of our authentic selves either. Rather we found it most satisfying to hold impulses and values as a dialectic, locating the authentic self in the tension between them. Based on our inquiry experiences, we found it plausible to extend that recovering or cultivating the authentic self may involve a process that begins with an emphasis on allowing impulses and reactions (i.e., those that were stifled in childhood and beyond) to be expressed, and after some time satisfying this need, extends towards impulse-modulation in light of values.[8] Consistent with our exploration of parts, this stance accepts that we may need to reclaim stunted impulses on the path of authenticity, while acknowledging the growth-orientation of the authentic self that may call us to express our deeper values. The key to disambiguating the relative authenticity of impulses and their value-based modifications, then, is identifying where we are in this process within a given domain of life. Thus, building on the previous theme, we found our authentic selves in both the wounded or triggered parts and their needs (e.g., the need to feel and express impulses) and in the often called “higher self” and core values inviting us to evolve.

Dynamism and Relationality

The closing theme addresses the dynamic and relational aspects of the authentic self. Without diminishing the other themes, we felt as though this one was foundational—like a containing substratum—of our experiences of our authentic selves.

Unfolding the dynamic quality first, all co-inquirers described a version of this experience, sharing variously that their authentic selves were, “responsive,” “process-oriented,” always “growing,” “evolving,” or in a “state of becoming.” Matt spoke directly to this quality, explaining that his experience of his authentic self was: “More as a verb than a noun, a constantly becoming, evolving, not a static fixed organization or state.” Similarly, Erica reported from her experience of: “[The] authentic self being a certain level of responsiveness to life that has fluidity to it… that is relevant to whatever is happening in the moment in a way that is intelligent.” Ashton movingly reflected in a similar tone at the end of our inquiry:

I believe that one must continue to ask themselves the question to live a full life, to actualize as much of one’s potential as possible—“What is my experience of my authentic self today?” Rather than a stopping point, a conclusive answer, I like to think of “authentic self” as a regulative ideal, a method for navigating the paradox of sameness and difference! Like Rilke, authentic self is a means of “living the questions.”

Consistent with these accounts, we came to a shared an understanding of the dynamic, responsive, and evolving nature of our experiences of our authentic selves.

Relatedly, we also experienced the authentic self as “embedded in relationships”—in terms of both the way that relationships evoke and help us to discover our authentic selves, and the way they mold and shape what is authentic for us in any given moment. Ashton contemplated the intrinsically relational orientation of the authentic self as he experienced it: “There’s something… in the experience of the authentic self… [that] feels bound up with being abandoned or rejected. So right away it feels bound up with others.” In this sense, it seemed impossible to us to isolate our experiences of our authentic selves from relationships. As Matt reported:

In my experience, who I am is always in response to someone else or to a situation. And if I just go in search of something authentic independently of a situation or the others that I’m in relationship with, I don’t find anything that I can articulate or grasp. I feel if the self is anything, if I am anything independent of my relations, it’s this… receptivity to situations, to others… It’s not like I don’t have my own desires and my own intentions… but even those are kind of formed in a relationship.

In a closing contemplation he furthered:

I came to see authenticity as a form of fluidity and creative responsiveness to changing relational contexts, and the “self” as a temporary mask or mirror called forth by specific contexts. There are many authentic selves within each of us. A self becomes inauthentic when it tries to stay on stage longer than it is welcomed, that is, longer than the relational context calls for it. Rather than finding one authentic self to respond to all situations with, I found that authenticity is largely about knowing when to shed selves that are no longer serving the creation of beauty or the relieving of suffering in any given moment.

Thus, in reflection on our process, we univocally agreed that our experiences of our authentic selves were alwaysrelational—whether that was our own relationship with ourselves, with others, or with the environment. This shared perspective was so strong, we set out to counter it using the devil’s advocate validity procedure (Heron, 1996) by attempting to argue for contradictory viewpoints. Yet, despite our sincere efforts to adopt alternative views (e.g., the authentic self is independent, unique, and pre-existing relationships; or solipsism, the premise that only the self can be known to exist), we could not sway our conviction that our experiences of our authentic selves were fundamentally relational.[9]

Within this theme of relationality, we also noticed the experience of our authentic selves unfolding into a sense of an “authentic group self.” Erika likened it to baking and explained:

There’s a way in which I feel… different in this group than I feel in other groups, so there’s a different [me] as a result of the chemistry of the ingredients of each one of us. So that’s the part of me that comes out and it’s interacting with the chemistry of others, and then we’re just creating something… none of us really know what it is, but it’s some kind of bigger self, like a collective self, and it feels like it has authenticity to it.

Ashton spoke to this phenomenon from another angle: “I had this vivid feeling of the group consciousness and almost as if it were bouncing through and expressing, something was expressing itself rhythmically through everybody based on the conditions of that person.”

While further exploration of this experience of the “group authentic self” or “group consciousness” spans beyond the present discussion, it conveys an interesting aspect of the relationally embedded authentic self as we experienced it and maybe of value for future research.

Transformative and Practical Outcomes

While the main aim of this article is to elucidate findings in response to the primary research question, I offer a brief discussion of transformative and practical outcomes to honor their significance in the context of CI, participatory, and transpersonal research. That is, transformative outcomes (i.e., the transformation of researchers, participants, and the research audience) are considered as, if not more, important than the informational or conceptual outcomes in CI (Heron, 1996) specifically, as well as in participatory (Heron & Reason, 1997; Reason, 1994a, 1994b; Reason & Bradbury, 2008) and transpersonal research (Anderson & Braud, 2011) in general. Specifically, I highlight a few accounts from co-inquirers that speak to the perceived impact of the inquiry first, followed by our reflections on the growth inspiring nature of the inquiry process in itself. Finally, I summarize the conditions that we found supportive of authenticity.

Speaking to the felt impact of the inquiry as we were engaging with it, several co-inquirers shared that the inquiry became a “backdrop” for daily life beyond the specific inquiry actions, with attention to authenticity guiding their sense of self and their interactions with others, thus, catalyzing personal growth. As Ashton reflected: “It’s almost like the question itself is a method for breaking the dam open and just seeing what comes, what keeps coming.” I proposed similarly: “The inquiry question—authentic self—if we put that on our map somewhere, or on our compass, just having it in the topography catalyzes something… it draws something more out… disrupts the train and something new can emerge.” Bill corroborated: “Asking the question allows me to pop out of this crazy train that I’m on, that we’re all on.” In this sense, co-inquirers discovered that being engaged in the inquiry fostered self-awareness in daily life, which, at times, converted into choices that supported authenticity and the expression of personal values or ideals, while supporting self-acceptance on the whole.

Reflecting on the inquiry process as a whole, several inquirers reported a sense of having positively changed as a result of the inquiry. For example, Erika reported, “I definitely know I am different as a result of doing this with you all.” She later reflected:

The process of the inquiry both alone doing practices and in the group was a rich exploration of how my definition manifested in real interaction with the world and with others… I definitely became more aware of the practices of my daily life that either naturally call forward my authentic self (i.e. meditation, dancing, working out, my work with clients…) and conversely the constraints and challenges of daily life that tend to… create obstacles to my being most in my authentic self (i.e. being in a hurry seems to be a challenge to whatever activity I’m in engaged in).

Ashton echoed: “Especially as a result of this group, I feel like I’m different,” and elaborated:

This process was tremendously significant—it coincided and facilitated a serious phase of maturation for me. The significance has much to do with learning. I have a tendency to put others on pedestals, but what our inquiry instilled in me was (is) the organic and collaborative process that is knowledge-making. Tremendously significant; tremendously empowering; tremendously humbling—empowering because I realized my own creative capacity to know (rather than absorb and imitate), humbling because I realized that we’re all in this together!

As these accounts communicate, participating in the inquiry had personal significance for co-inquirers, supporting their growth and transformation beyond the conceptual learning regarding the experience of the authentic self that is emphasized in this article.

Beyond our specific inquiry focus, numerous accounts suggested that the CI process in itself was growth inspiring. For example, Ashton reflected: “I feel like there’s something about the inquiry approach [holding an] attitude of ‘knowledge making’ as a communal effort… [T]here’s something really beautiful about that… It feels humanizing.” Additionally, co-inquirers reported experiencing the group as “nourishing.” This perceived nourishment was likely based on the foundation of mutual care (cf. Lahood, 2010, 2013), presence, desire to be there, and a sense of belonging that we cultivated in our group, which was a missing experience for some of us in childhood. Further, it seemed as through sharing the responsibility of witnessing and supporting each other in the group allowed us to relax and “feel held” both when sharing and listening (in contrast with the one-on-one interaction typical for the counselors in the group). I contemplated: “Perhaps, the nervous system can rest in the group in a way that we can’t on our own as self-reliant people in a hyper-individualistic culture?” Thus, we attributed some of the experiential benefits we enjoyed to the conscious group process that contained, yet extended beyond, the specific inquiry focus.

Finally, the inquiry yielded the practical outcome of capturing the conditions that co-inquirers found to support authenticity in our CI process. Specifically, co-inquirers highlighted the following conditions: safety, trust, playfulness or an exploratory attitude, a caring or compassionate ethos in the group, welcoming expression of repressed parts, the presence of caring witnesses, vulnerability, reciprocity, and open time. Further analysis and elaboration of these conditions, as well as future research to assess their potential broader application to authentic self exploration or group work in general, may be fruitful.

Conclusion

The present study explored the experience of the authentic self through CI—a research methodology with a phenomenological, participatory, and transformative emphasis. Through this collaborative process, co-inquirers generated six themes addressing their experiences of their authentic selves, including presence and flow, somatic awareness and vitality, expression of truth, multiple parts and integration, impulses and values, and dynamism and relationality. Overall, we came to a radically inclusive framework that ultimately recognized the authenticity of all of our experiences of self. At the same time, we found it plausible to locate the authentic self concept (vs. the actual, experiential authentic self) at the intersection of the ideal and real, perhaps as an integrative or regulative principle that is oriented toward growth given supportive conditions. We also found our experiences of our authentic selves as fundamentally relational, suggesting that authenticity is intimately connected with interpersonal and environmental contexts. Finally, co-inquirers reported meaningful personal benefit and positive change from the inquiry attributed to both the specific inquiry focus as well as the inquiry process in general.

These findings were largely consistent with humanistic perspectives that recognize the dynamic, growth-oriented nature of the authentic self as a process of becoming (e.g., Maslow, 1954/1970; Rogers, 1961). However, our findings also suggest that the authentic self is more embedded in relationship and environment than is intimated by humanistic and popular notions of authenticity that emphasize individuality and self-definition apart from social influences (see note 9). That is, while our inquiry findings supported the significance personal truth and values—which may, at times, differ from external context—they also emphasized interconnection and participation with others and the environment in the cultivation and expression of the authentic self.

The robust conceptual and transformative outcomes of this inquiry suggest promising avenues for future research. First, because CI generates participatory knowledge (i.e., knowledge that is cocreated and contextual versus objective or universal), replication of this inquiry with diverse individuals and social groups (i.e., groups organized around social identities, within psychospiritual communities holding divergent pre-understandings of the authentic self, different age groups) would likely expand and deepen these outcomes. Further, given the interpersonal nature of CI, it may be illuminating to compare the relational emphasis of these findings with outcomes from individually focused research methods or CIs using more solitary actions during inquiry cycles (e.g., meditation, alone time). In addition, future inquiries could go beyond elucidating the authentic self as experienced, to explore, for example, the perceived value of cultivating the authentic self or optimal approaches that may foster authentic self knowledge and expression. Finally, putting these findings into dialogue with existing theoretical and empirical literature would also be fruitful to deepen this discussion and inform future research.

In closing, I offer several implications of this authentic self inquiry for therapeutic and educational practice with individuals and groups. With individual clients, these findings could be applied to explore their relationship to authenticity. If, for example, they were significantly, thwarted in their self-expression in childhood or in current circumstances, encouraging them to focus on feeling and expressing their impulses, developing personal autonomy, and taking discerning risks to counter external expectations maybe supportive. In contrast, a more individualistically oriented or self-reliant client might be encouraged to explore relational values (e.g., harmony, kindness, compassion) as a matter of maturing the authentic self. In addition, the outcomes of this inquiry suggest that this kind of process could be a fruitful foundation for facilitated or peer-based group therapeutic or personal-growth work.

Notes

[1] In this article, the term authentic self refers to the general psychospiritual and popular notion that individuals can experience and express a sense—or essence—of self that feels more subjectively “real” or “true,” in contrast with false or externally influenced self representations, expressions, or behaviors. Authentic self is used here synonymously with the related concept of the “true self,” which appears to be more prominent in contemporary psychological research and Eastern traditions.

[2] Importantly, connecting these diverse theories and traditions does not mean to suggest that they understand the authentic self in the same way or even refer to the same ontological referent. Rather, this research recognizes that there are innumerable perspectives on the self, with nearly all spiritual and psychological traditions positing a stance on the issue giving rise to volumes of discussion and debate on the self (e.g., Baumeister, 1999; Siderits et al., 2011; Zahavi, 2014). Perspectives range from a rejection of an enduring authentic self—as in certain forms of Buddhism (e.g., Albahari, 2006; Thubten, 2013; Loy, 2019), social constructivism (e.g., Gergen, 1991; Mead, 1934/2015), and strains of analytical philosophy (e.g., Metzinger, 2009)—to claims that the discovery and cultivation of one’s authentic self is the ultimate attainment of psychospiritual growth (e.g., Joseph, 2016; Miller, 1979; Rogers, 1961; Winnicott, 1960). In some perspectives, the Self points to a shared spiritual or transpersonal dimension (e.g., Assagioli, 1993; Bache, 2000; Daniels, 2005) or a process (e.g., Thomson, 2015), while in others the notion of authentic self suggests that each individual possesses a unique kernel of potential that is essential to his or her fulfillment in life (e.g., Cope, 2012; Hillman, 1996). And still in others, the self is considered to be forged largely by the environmental and sociocultural context (e.g., Gergen, 1991; Mead, 1934/2015). From these vastly diverging—and yet, not mutually exclusive (see, e.g., Zhavi, 2014)—views, one is left to wonder whether this idea of an authentic self is a social construct, a psychological concept, or a spiritual reality. While important, this line of questioning is bracketed within this research.

[3] Although beyond the scope of this study, it is important to acknowledge the active debate in the historical and contemporary psychological literature regarding the ontological status of the authentic self (and the self in general). In short, perspectives diverge between claims that posit a real authentic self that actually exists (i.e., veridical; e.g., Kernis & Goldman, 2006; Rogers, 1951, 1961; Sheldon, 2014) to perspectives that hold the construct as a, perhaps, psychosocially useful falsehood (i.e., nonveridical; e.g., Baumeister, 2019), respectively (see Rivera et al., 2019 for a discussion of these divergent stances). The present inquiry brackets ontological claims regarding the authentic self—neither assuming the reality of a unified authentic self nor denying the possibility—to focus on the phenomenological experience of the authentic self as explored by seven co-inquirers. In this sense, this study emphasized the subjective experience of authenticity or the emerging construct of “state authenticity” (Lenton et al., 2016; Lenton, Bruder et al., 2013; Sedikides et al., 2017).

[4] Given the common recruitment sites, all participants were at least acquainted with one other person in the group, with some knowing each other quite well already, including two couples. In CI, as with many forms of participatory research, it is common for co-inquirers to have pre-existing relationships and/or dual relationships with each other and/or the initiating researcher (e.g., friends, peers, professional colleagues). In the participatory research context, unlike some other forms of qualitative research, this is not considered a hinderance to research validity.

[5] It is important to note that our inquiry actions (see Table 1; cycles 1 and 3) centered around the attempt to engage with each other while suspending or bracketing the “socialized self,” were held with a curious, exploratory attitude, and without expectation that we might fully “succeed” at this effort. We set up this action phase by first discussing what we might be suspending (e.g., talking about the past, future, other people not in the room, our professional roles) and what we might emphasize (e.g., sharing felt sensations, emotions, and thoughts arising in the present moment). Then we set a timer to give it a try. Certainly, there were moments of collective confusion and meta-commentary (i.e., “I don’t know if this is ‘socialized’ or not…”) within the allotted time and such discussions were integral to our reflection conversations. Several of us were aware of philosophical debate regarding the implausibility of accessing a self somehow untouched by socialization (e.g., Gergen, 1991; Mead, 1934/2015) and our experiences demonstrated the difficulty of this exercise. At the same time, however partial our bracketing may have been, the attempt engendered a fertile group dynamic in which we had a chance to see and reveal ourselves, and witness each other, in meaningful ways. We were left curious about what would happen if this prompt had been repeated numerously but chose to continue on to different actions in subsequent inquiry cycles.

[6] During the first full day of inquiry, we collaboratively determined and adopted the following group guidelines: (a) compassion, mutual care, respect, and confidentiality; (b) openness and curiosity; (c) presence and mindfulness; (d) honesty; (e) courage, willingness to engage creative challenge; (f) transparency and communication about time management.

[7] Clear parallels can be made between our experiences of multidimensionality and psychological systems that recognize and work directly with multiple parts of self, such as Internal Family Systems (Schwartz, 1995), psychosynthesis (Assagioli, 1993), and Bromberg’s (2006) multiple self-states models, among others. Related trends highlighting multiple, contextual, or relationally contingent selves—or rather self-concepts (see Baumeister, 2019)—are prominent in contemporary authenticity research (e.g., Chen, 2019, Oyserman et al., 2015). While extending beyond the present discussion, these parallels suggest that contextualizing our findings in light of existing authenticity literature and research would be a worthwhile basis for future elaboration.

[8] Note that we do not imply that this process of authentic self recovery and exploration is entirely linear, something that is experienced once and then complete, or consistent within different contexts. Rather, engaging the dialectic between impulses and values is likely cyclical, or spiraling, and may involve different levels of development within different domains of life (e.g., intimate relationships versus career).

[9] Due to space limitations, the present article does not contextualize these findings in light of the existing literature and research on the authentic self, but it is worth noting that the relational emphasis of our inquiry marks an important domain for future elaboration. While this emphasis may run contrary to certain individualistic interpretations of the authentic self in founding humanistic theory (i.e., the authentic self as standing apart from, or independent of, sociocultural influences; e.g., Maslow, 1954/1970; Rogers, 1961), this finding aligns with contemporary calls for a sociocultural turn in humanistic psychology (McDonald & Wearing, 2013), as well as the participatory turn in transpersonal psychology (Ferrer, 2002, 2017) and trends in contemporary authenticity research that hold the self as contextual or relational (e.g., Chen et al., 2019; Rivera et al., 2019).

References

Albahari, M. (2006). Analytical Buddhism: The two-tiered illusion of self. Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson, R., & Braud, W. (2011). Transforming self and others through research: Transpersonal research methods and skills for the human sciences and humanities. SUNY Press.

Assagioli, R. (1993). Psychosynthesis: The definitive guide to the principles and techniques of psychosynthesis. Thorsons.

Bache, C. (2000). Dark night, early dawn: Steps to a deep ecology of mind. SUNY Press.

Baumeister, R. (2019). Stalking the true self through the jungles of authenticity: Problems, contradictions, inconsistencies, disturbing findings—And a possible way forward. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 143–154.

Baumeister, R. M. (Ed.) (1999). The self in social psychology. Taylor and Francis.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Bromberg, P. M. (2006). Awakening the dreamer: Clinical journeys. Analytic Press.

Brown, B. (2010). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Hazelden Publishing.

Bryan, J. L., Baker, Z. G., & Tou, R. Y. W. (2017). Prevent the blue, be true to you: Authenticity buffers the negative impact of loneliness on alcohol-related problems, physical symptoms, and depressive and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, 22, 605–616.

Chen, S. (2019). Authenticity in context: Being true to working selves. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 60–72.

Cope, S. (2012). The great work of your life: A guide for the journey to your true calling. Bantam Books.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial.

Daniels, M. (2005). Shadow, self, spirit: Essays in transpersonal psychology. Imprint Academic.

English, T., & John, O. P. (2013). Understanding the social effects of emotion regulation: The mediating role of authenticity for individual differences in suppression. Emotion, 13, 314–329.

Ferrer, J. N. (2002). Revisioning transpersonal theory: A participatory vision of human spirituality. SUNY Press.

Ferrer, J. N. (2017). Participation and the mystery: Transpersonal essays in psychology, education, and religion. SUNY Press.

Feurstein, G. (2001). The Yoga tradition: It’s history, literature, philosophy, and practice. Hohm Press.

Fleeson, W., & Wilt, J. (2010). The relevance of Big Five trait content in behavior to subjective authenticity: Do high levels of within-person behavioral variability undermine or enable authenticity achievement? Journal of Personality, 78, 1353–1382.

Gergen, K. (1991). The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. Basic Books.

Heron, J. (1996). Co-operative inquiry: Research into the human condition. Sage Publications.

Heron, J., & Reason, P. (1997). A participatory inquiry paradigm. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(3), 274-294.

Heron, J., & Reason, P. (2006). The practice of co-operative inquiry: Research ‘with’ rather than ‘on’ people. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (pp. 144-154). Sage Publications.

Heron, J., & Reason, P. (2008). Extending epistemology within a co-operative inquiry. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd ed., pp. 366-380). Sage Publications.

Hicks, J. A., Newman, G. E., & Schlegel, R. J. (Eds.). (2019). Authenticity: Novel insights into a valued, yet elusive, concept. [Special issue].Review of General Psychology, 23(1).

Hicks, J. A., Schlegel, R. J., & Newman, G. E. (2019). Introduction to the special issue: authenticity: novel insights into a valued, yet elusive, concept. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 3-7.

Hillman, J. (1996). The soul’s code: In search for character and calling. Random House.

James, W. (1890). The consciousness of self. The principles of psychology, vol I; the principles of psychology, vol I. (pp. 291-401). Henry Holt and Co.

Jongman-Sereno, K. P., & Leary, M. R. (2019). The enigma of being yourself: A critical examination of the concept of authenticity. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 133–142.

Joseph, S. (2016). Authentic: How to be yourself and why it matters. Piatkus Little-Brown.

Joseph, S. (2017). The real deal. Psychologist, 30(1), 34-37.

Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity:

Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 283–357.

Lahood, G. (2010). Relational spirituality, part 2: The belief in others as a hindrance to enlightenment: Narcissism and the denigration of relationship within transpersonal psychology and the New Age. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 29(1), 58-78.

Lahood, G. A. (2013). Therapeutic democracy: The roots and potential fruits of a Gestalt- assisted collaborative inquiry. Gestalt Review, 17(2), 119-148.

Lahood, G. (2019). The rainbow of desire: Seven-years practicing seven relationships in relational co-inquiry. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies.

Lenton, A. P., Bruder, M., Slabu, L., & Sedikides, C. (2013). How does “being real” feel? The experience of state authenticity. Journal of Personality, 81, 276–289.

Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., Sedikides, C., & Power, K. (2013). I feel good, therefore I am real:

Testing the causal influence of mood on state authenticity. Cognition & Emotion, 27, 1202–1224.

Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., & Sedikides, C. (2016). State authenticity in everyday life. European Journal of Personality, 30, 64–82.

Lopez, F. G., & Rice, K. G. (2006). Preliminary development and validation of a measure of relationship authenticity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 3, 362–371.

Loy, D. (2019). Nonduality in Buddhism and beyond. Wisdom Publications.

Maslow, A. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd edition). Harper & Row. (Original work published in 1954).

McDonald, M., & Wearing, S. (2013). A reconceptualisation of the self in humanistic psychology: Heidegger, Foucault and the sociocultural turn. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 44(1), 37-5.

Metzinger, T. (2009). The ego tunnel: The science of the mind and the myth of the self. Basic Books.

Mead, G. H. (2015). Mind, self and society: The definitive edition. University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1934).

Miller, A. (1979). The drama of the gifted child: The search for the true self. Basic Books.

Murphy, D., Joseph, S., Demetriou, E., & Karimi-Mofrad, P. (2017). Unconditional positive self-regard, intrinsic aspirations, and authenticity: Pathways to psychological well-being. Journal of Humanistic Psychology,1-22. Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167816688314

Naranjo, C. (2004). Gestalt therapy: The attitude and practice of an atheoretical experientialism (2nd ed.). Crown House Publishing.

Neff, K. D., & Suzio, M. A. (2006). Culture, power, authenticity and psychological well-being within romantic relationships: A comparison of European American and Mexican Americans. Cognitive Development, 21, 441–457.

Newman, G. E. (2019). The psychology of authenticity. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 8–18.

Oyserman, D., Destin, M., & Novin, S. (2015). The context-sensitive future self: Possible selves motivate in context, not otherwise. Self and Identity, 14(2), 173–188.

Perls, F. (1968). Gestalt therapy verbatim. Real People Press.

Perls, F., Hefferline, R. F., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt therapy: Excitement and Growth in the human personality. Gestalt Journal Press.

Plato. (2018). The dialogues of Plato (B. Jowett, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1892).

Polkinghorne, D. (2001). The self and humanistic psychology. In K.J. Schneider, J. F. T. Bugental & J. F. Pierson (Eds.), The handbook of humanistic psychology: Leading edges in theory, research and practice (pp. 81-99). Sage Publications.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2008). The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd edition). Sage Publications.

Reason, P. (Ed.). (1994a). Participation in human inquiry. Sage Publications.

Reason, P. (1994b). Co-operative inquiry, participatory action research and action inquiry: three approaches to participative inquiry. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 324-339). Sage Publications.

Rivera, G. N., Christy, A. G., Kim, J., Vess, M., Hicks, J. A., & Schlegel, R. J. (2019).

Understanding the relationship between perceived authenticity and well-being. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 113–126.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Constable.

Rosenberg, J. (2019). Be true: A personal guide to becoming your most authentic self. Enlightened Leadership Publishing.

Rowan, J. (1993). The transpersonal: Psychotherapy and counselling. Routledge.

Schlegel, R. J., & Hicks, J. A. (2011). The true self and psychological health: Emerging evidence and future directions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(12), 989-1003.

Sedikides, C., Slabu, L., Lenton, A., & Thomaes, S. (2017). State authenticity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 521-525.

Sheldon, K. M. (2014). Becoming oneself: The central role of self-concordant goal selection. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 349–365.

Schwartz, R. C. (1995). Internal family systems. Guilford.

Siderits, M., Thomson, E., & Zahavi, D. (Eds.). (2011). Self, no self? Perspectives from analytical, phenomenological, and Indian traditions. Oxford University Press.

Stevens, F. L. (2017). Authenticity: A mediator in the relationship between attachment style and affective functioning. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 30(4), 392–414.

Strohminger, N., Knobe, J., & Newman, G. (2017). The true self: A psychological concept distinct from the self. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 551–560.

Thomson, E. (2015). Waking, dreaming, being: Self and consciousness in neuroscience, meditation, and philosophy. Columbia University Press.

Thubten, A. (2013). No self, no problem: Awakening to our true nature. Shambhala Publications.

Von Franz, M.-L. (1964). The process of individuation. In C. G Jung (Ed.), Man and his symbols (pp. 158-229). Doubleday & Company Inc.

Wickham, R. E., Williamson, R. E., Beard, C. L., Kobayashi, C. L., & Hirst, T. W. (2016). Authenticity attenuates the negative effects of interpersonal conflict on daily well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 60, 56–62.

Winnicott, D. W. (1960). Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. In D. W. Winnicott (Ed.), The maturational process and the facilitating environment (pp. 140–152). International Universities Press.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the Authenticity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385.

Zahavi, D. (2014). Self and other: Exploring subjectivity, empathy, and shame. Oxford University Press.

Zhang, H., Chen, K., & Schlegel, R. J. (2018). How do people judge meaning in goal-directed behaviors: The interplay between self-concordance and performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(11), 1582-1600.